FDA Accepted Alternatives to Nonclinical Testing in Primates

December 4, 2025

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has long been committed to advancing the application of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in nonclinical testing. Guided by the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement). NAMs aim to enhance the predictivity of clinical outcomes while reducing reliance on traditional animal studies. Encompassing in vitro, ex vivo, and in silico technologies, NAMs have gradually emerged as core tools for evaluating the safety and efficacy of pharmaceuticals [1].

This article systematically explores the regulatory framework underpinning NAMs, showcases FDA-endorsed technical implementations and case studies, outlines core evaluation criteria from FDA’s review perspective, examines global regulatory convergence, and addresses key challenges alongside forward-looking regulatory strategies—providing actionable insights for pharmaceutical stakeholders navigating nonclinical testing innovation.

Policy and Framework: Regulatory Foundations for NAMs

Core Policy Support

|

Release Time |

Policy Name/Initiative |

Core Content |

|

Passed by the U.S. Senate in September 2022, final approved by the U.S. House in December 2022 |

Repeals the statutory mandate for mandatory animal testing of new drugs; permits alternative methods based on human biology (e.g., microphysiological systems, computational models) for drug testing. |

|

|

Introduced in February 2024, – passed by the U.S. Senate in December 2024 |

Further advances FDA Modernization Act 2.0 by incentivizing NAMs (e.g., organoids, organ chips) in preclinical assessments and establishing cross-agency coordination for method validation. |

|

|

April 2025 |

Roadmap for Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies |

Outlines a phased strategy; prioritizes mAb and biologic pilot programs; encourages NAMs data submission; establishes an international database for global regulatory alignment. |

Definition and Core Traits of NAMs

FDA defines NAMs as nonclinical tests conducted via in vitro, in silico, or other non-animal approaches. Their core traits include improving clinical predictivity, reducing animal usage, and prioritizing human-relevant data. NAMs cover the entire drug development lifecycle—from toxicity screening and efficacy evaluation to risk characterization—with typical technologies including complex in vitro models (CIVM), quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, and Weight of Evidence (WoE) assessments[1].

Cases Studies: Technical Implementation and FDA-Endorsed NAMs

Mature Technologies with Regulatory Endorsement

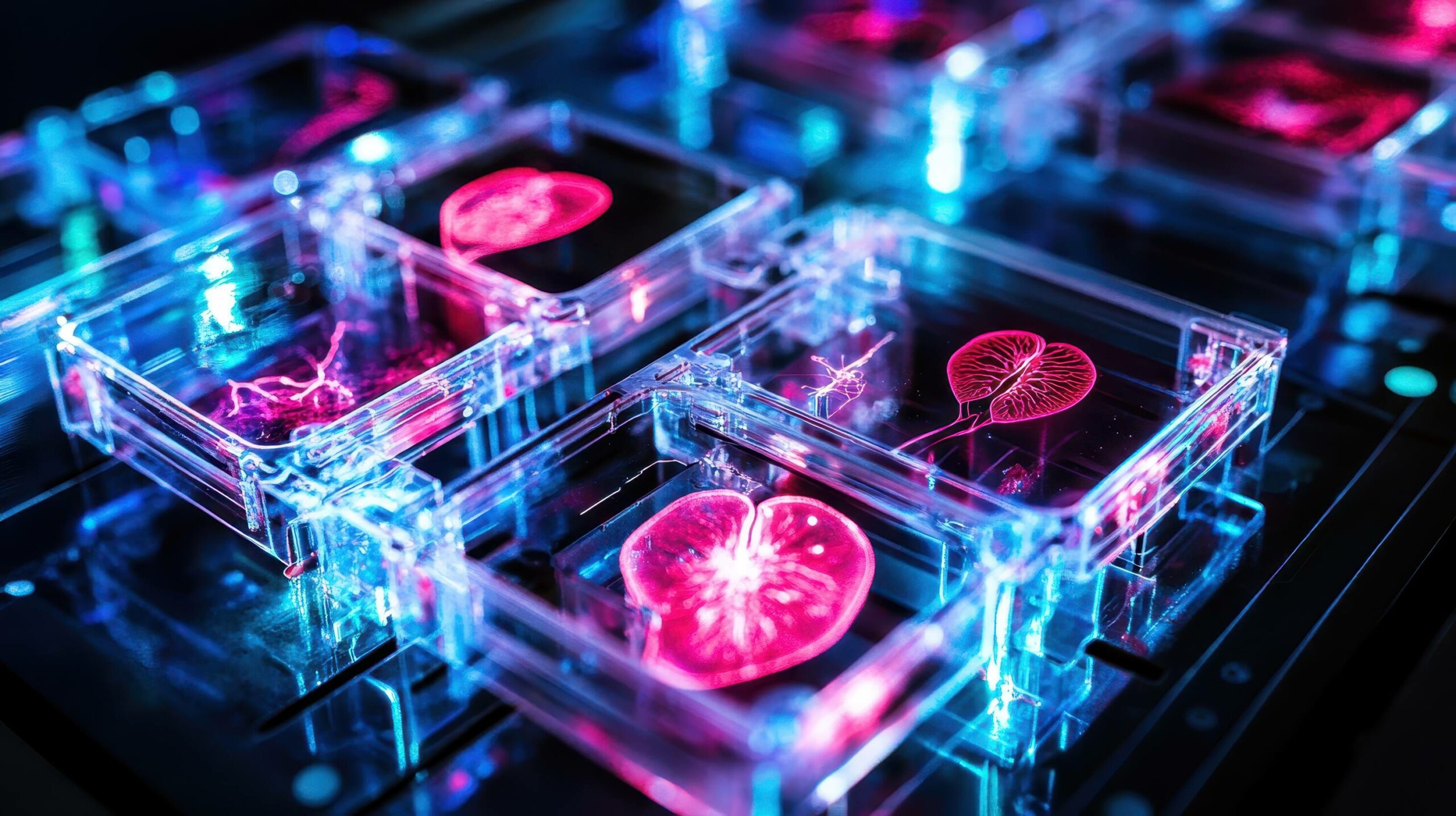

- In Vitro Assays Replacing Animal Tests: The Bovine Corneal Opacity and Permeability (BCOP) test and 3D Reconstructed Human Cornea-Like Epithelium (RhCE) model have replaced rabbit eye irritation studies and been incorporated into OECD Test Guidelines. In vitro skin irritation and phototoxicity tests using 3D skin models have reduced the use of non-rodent animals by over 40%. Organ-on-a-Chip Systems have earned formal FDA backing: Sanofi’s drug Sutimlimab for the treatment of Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP) that obtained preclinical efficacy data from human organ‐on‐a‐chip to enter Phase II clinical trials, in conjunction with existing safety data. This marked the first official recognition of the use of organoid chips as an alternative to animal experiments. Emulate’s Liver-Chip S1 is the first Organ-Chip technology to be accepted into the FDA’s ISTAND Pilot Program for prediction of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) screening from 6+ months (NHPs) to 14 days and eliminates redundant toxicity testing for antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)[6].

- Computational Toxicology Models: ICH M7(R2) guidelines specify that QSAR models can predict the genotoxicity of drug impurities. The FDA has used these models to assess the carcinogenic risk of N-nitrosamine impurities and establish acceptable intake limits.

- Comprehensive In Vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA): Integrating human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) and in silico modeling, CiPA accurately predicts drug-related cardiovascular risks and has been used in IND submissions and labeling.

Typical Drug Approval Cases

|

Drug |

Indication |

NAM Application Method |

Regulatory Impact |

|

Kalydeco |

Cystic Fibrosis |

In vitro CFTR chloride transport assays; bronchial organoid functional assessment |

Expanded to specific gene variants without additional clinical trials |

|

Galafold |

Fabry Disease |

In vitro α-Gal A activity assays; renal organoid mutant protein evaluation |

Approved for more genetic subtypes based on activity thresholds |

|

Veopoz |

CHAPLE Disease |

In vitro complement system inhibition assays + ex vivo CH50 hemolysis assay |

Approved without relevant animal models, supported by mechanistic data |

|

Kimmtrak |

Uveal Melanoma |

Human tissue/cell-based in vitro assays (target binding specificity) |

Validated targeting/safety, overcoming animal model limitations |

Weight of Evidence (WoE) Assessment

By integrating analytical similarity data, human pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data, and clinical outcomes, WoE assessments replace traditional animal studies in key scenarios:

- Carcinogenicity Assessment: Replaces 2-year rat carcinogenicity studies (reducing usage by over 400 animals) and has been endorsed by ICH S1B(R1).

- Reproductive Toxicity Assessment for Oncology Drugs: Combines drug mechanism of action, data from similar drugs, and in vitro embryotoxicity assays to waive some animal studies.

- Biosimilar Approval: Adalimumab biosimilars (e.g., Cyltezo[9]) obtained approval via the WoE framework without nonhuman primate toxicity testing (consistent with WoE logic in).

Review Perspective: Core FDA Evaluation Dimensions for NAMs

FDA pharmacology/toxicology reviewers evaluate NAM-submitted data across five key dimensions to ensure scientific rigor[10]:

- Context of Use (COU): The specific purpose of NAMs (e.g., DILI risk prediction, target binding validation) must be clearly defined to avoid overly broad study objectives.

- Biological Relevance: Models must simulate human physiological/pathological states, with endpoints directly linked to clinical outcomes (e.g., bile acid accumulation in liver chips as a marker of DILI risk).

- Technical Characterization: Detailed descriptions of study design, control settings, and method reproducibility are required to enable independent validation of data.

- Data Integrity: Data complying with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and OECD Good In Vitro Method Practices (GIVIMP) is preferred, with clear documentation of experimental deviations and their impacts.

- Transparency: Raw data, methodological details, and peer-reviewed materials must be submitted to facilitate reviewer assessment of technical reliability.

Global Convergence in Primate Testing Replacement

- European Union: The EU’s “Vitro Cellomics” project validated human cell lines for immunotoxicity testing, sharing methodological standards with the FDA.

- Asia-Pacific: China’s NMPA, South Korea’s MFDS, and Japan’s JaCVAM, have all adopted ICH guidelines, endorsing NAM data (e.g., organ chips, WoE assessments) to facilitate cross-border drug application mutual recognition.

Challenges and Regulatory Path Forward

Despite progress, NAMs application faces key challenges:

- Technical: Vascularized organoids/multi-organ chips lack standardization.

- Industry: High NAMs upfront costs; limited expertise; hesitancy to adopt unproven methods.

- Global: Inconsistent validation criteria across regions.

To address these gaps, the FDA has rolled out targeted solutions: establishing rigorous NAM validation criteria tailored to specific use cases, building a cross-agency data repository to centralize performance data, and offering regulatory incentives such as priority review for NAM-derived data to accelerate industry application.

Conclusion

FDA’s NAM endorsement shifts nonclinical testing to human-centric, ethical, and efficient practices. Global regulatory alignment and tech advances will further reduce primate reliance, balancing science, ethics, and patient access to safe drugs.

How BLA Regulatory can help?

With deep expertise and rich experience in global regulatory affairs, BLA Regulatory can guide you through regulatory strategy to execution by building up BLA/NDA from solid IND strategy.

References

- (2025). CDER Information on Alternative and Reduced Animal Testing. https://www.fda.gov/media/182478/download?attachment

- (2025). Roadmap for NAM Integration in Drug Development. https://www.fda.gov/media/186092/download

- (2025). Guidance on Weight of Evidence Assessment. https://www.fda.gov/media/159235/download

- Emulate Inc. (2023). Liver Chip Regulatory Clearance Documentation for DILI Screening. FDA Premarket Notification (510(k)) Summary. https://emulatebio.com/liver-chip-accepted-into-fda-istand-pilot-program-lorna-ewart-interview/

- Wang et al. (2024) Complex in vitro model: A transformative model in drug development and precision medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10828975/

- FDA (2022). CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND BIOPHARMACEUTICS REVIEW(S) of 215457Orig1s000. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/215457Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf

- FDA (2021). FDA Approves Cyltezo, the First Interchangeable Biosimilar to Humira. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USFDA/bulletins/2f802cd

- Yao et al. (2025). FDA/CDER/OND Experience With New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41231273/